Local politics have risen in importance during the Covid-19 pandemic era. Parents who may have previously thought little about education issues are now directly impacted by Covid-related policy decisions – and many have been spurred by the challenges of the pandemic to take a more active role in their children’s education.

The significance of this shift was made clear during the 2021 Virginia gubernatorial race – when Republican candidate Glenn Youngkin pulled out an upset victory over Democrat Terry McAuliffe by campaigning on a number of education related issues. Parents were outraged by allegations that the Loudon County School Board pressured the family of a high school girl who was was raped by a transgender student in a school bathroom to keep silent. McAuliffe put the nail in his gubernatorial campaign’s coffin when he said “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach” in a debate with Youngkin following the incident.

South Carolina is no stranger to school board controversies and surging parental involvement. Just last month, I reported on allegations that Richland two superintendent Barron R. Davis physically accosted a parent during a school board meeting. I’ve also recently reported on shocked Palmetto State parents demanding to know why their children’s school library contained a book which graphically depicts children having incestuous sex.

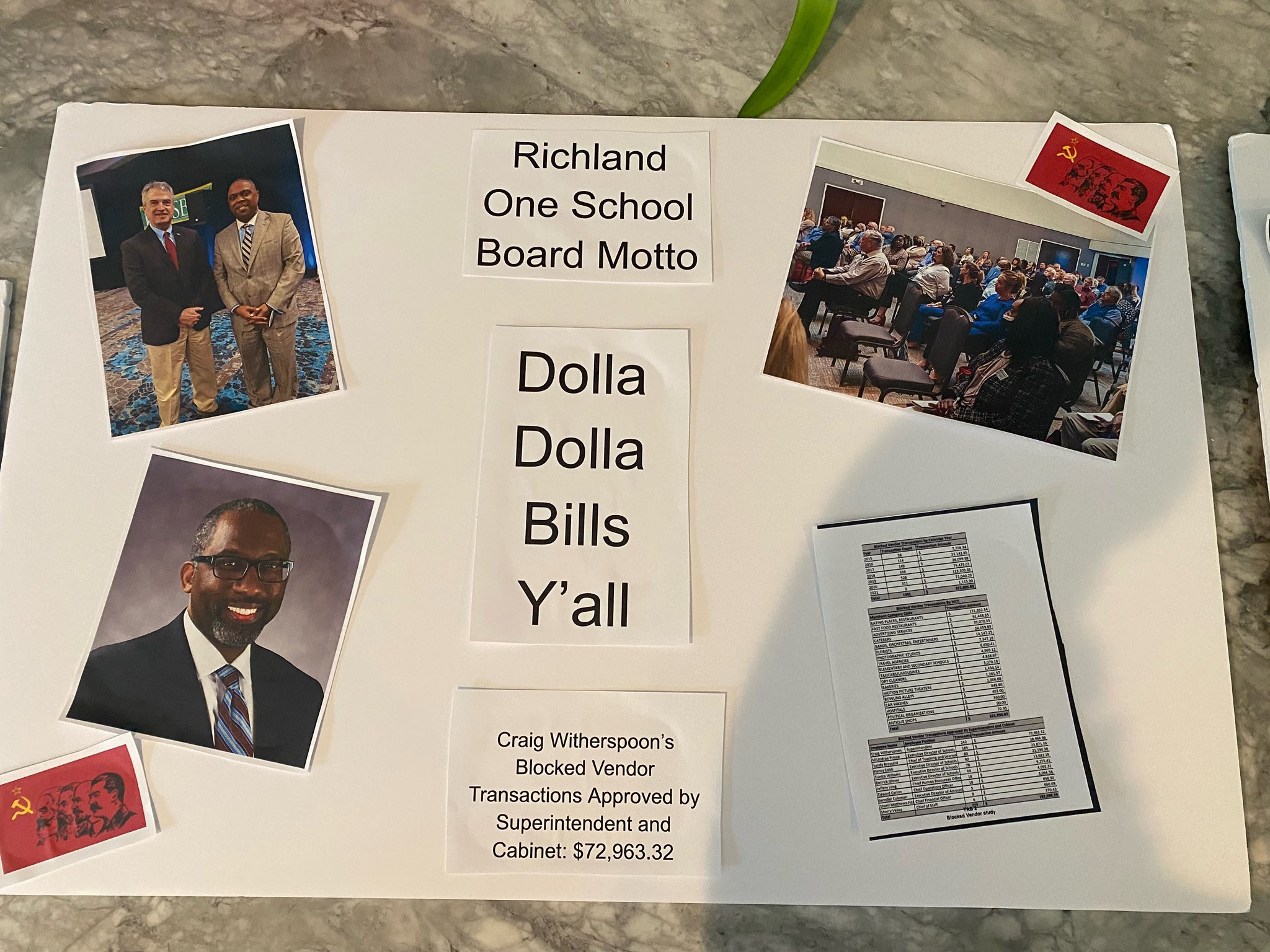

A growing number of parents of children in Richland County school district one in Columbia S.C. have become increasingly frustrated by the district’s Covid policy – and by allegations that district employees have misappropriated thousands of dollars through the fraudulent use of expense cards.

Richland one is “South Carolina’s ninth-largest school district, with 52 schools and centers, 22,000 students in pre-K through twelfth grade and 4,200 employees,” according to the district’s website.

The district currently forces all 22,000 of those students to wear masks, which has become increasingly unpopular as businesses and governmental entities around the country drop their mask requirements. Parents became particularly incensed when photos of board members attending the recent South Carolina School Board Association conference maskless circulated on social media.

(Via: @ColaSCWatchDog Twitter)

Mask controversies aren’t the district’s only issue. A report released by concerned citizens who obtained and analyzed the district’s purchase card (P-card) records concluded that there is “a culture of fraudulent P-card use in Richland district one with little to no interest by District leadership in exercising their supervision and accountability responsibilities.”

One year ago, Richland county councilwoman Dalhi Myers was indicted by a statewide grand jury on multiple public corruption charges, some of which stemmed from P-card misuse resembling what the report alleges may be occurring in Richland district one.

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests made by concerned parents showed the district’s own internal auditor found violations and infractions of $148,003 upon sampling a modest eight percent of transactions.

Violations included splitting charges to bypass district policy that requires bidding on large purchases. The auditor’s report concluded “cardholders circumvented single purchase limits by splitting transactions into two or more segments to stay within their single purchase limit, which violates procedural controls.”

The district’s policy states that violations of these procedures require termination of the employee’s P-card, yet a FOIA submitted to the school asking for records of P-card closures showed that no accounts were closed in the year of the audit, the year before the audit, or the year after the internal audit.

The internal auditor’s report cautioned “the total (potential violations) represents a small percentage of the total budget, so the financial risk may not be significant.”

“However, the control deficiencies noted in the review potentially increase regulatory risk, and the risk of adverse public relations,” the report continued.

I spoke with Richland district one spokesperson Karen York on February 24th. York confirmed receipt of questions related to these incidents on the 24th, but has yet to provide a response on the behalf of the district.

One of the parents involved in producing the report told FITSNews the document was initially circulated to legislators, to the S.C. State Law Enforcement Division (SLED) and to the office of the attorney general Alan Wilson, but that no one had the authority to investigate further. The group of parents who put the report together were particularly shocked when a representative of the investigator general’s office told them school boards were “not a part of their jurisdiction.”

This parent told me “once we learned the fox isn’t watching the hen-house … nobody is watching the hen house” they decided “If we can’t get the government to help us we will just have to tell people.”

And so this group of parents – who asked to remain unidentified because they fear the district will retaliate against their children – decided to publish their report. The document circulated on social media and inspired parents who attended last week’s school board meeting to demand an independent audit of the district’s finances.

One parent’s sign illustrated the collective frustration of many of the parents who attended the meeting.

(Click to view)

(Via: @SCColaWatchdog)

Are the parents justified in their outrage over these transactions? Given Richland district one’s long history of financial shenanigans it certainly isn’t out of the question, but it is impossible to know for sure. There are currently no mechanisms in place to facilitate audits of school districts by an impartial outside entity – or to remove school board members who abuse their office.

The lack of substantive financial oversight goes a long way in explaining why despite total per pupil funding of $17,678 South Carolina still sufferers from stagnant test scores and poor student outcomes. One Richland district one parent told me “they are graduating kids who aren’t ready to go into the workforce or into college” adding that “until we can get these kids into jobs the school to jail pipeline will be huge.”

H. 3069, pre-filed in December of 2020 and currently in the house judiciary committee, is designed to bring accountability to school boards by “authorizing the state inspector general to conduct financial and forensic audits of school districts.” One lawmaker who sponsored the bill told FITSNews the legislation “just makes sense, at least to those of us with nothing to hide.”

“If you don’t want to be accountable for how you spend taxpayer money, don’t take a job where you spend taxpayer money,” state representative Micah Caskey told me. “It only makes sense, to me, that the General Assembly takes this smallest of steps to make sure we know we’re being told the truth about where taxpayer money is actually going.“

***

Another bill – S. 203 – proposes school district trustees who are perpetually absent, neglect their duties, show conflicts of interest or who persistently neglect the duties of their office be subject to removal by the governor following a written notification and opportunity to make their case heard.

Senator Sean Bennett, a sponsor of S. 203, told FITSNews the bill was critical to restoring public faith in the leadership of South Carolina’s taxpayer-funded schools.

“A great deal of trust is granted to those who set policy for the schools that educate our children,” Bennett said. “When people break that trust they must be held accountable. We must have confidence that policy decisions are student focused and that all hands are on deck in the fight to improve learning outcomes.”

In rebuking Richland district two administrators recently, I wrote “if education in Richland district two – and across the Palmetto State – is ever going to improve, then parents better start paying closer attention to the kinds of people they elect to their children’s school boards. Absent that, they should consider running themselves if the only people filling these posts are self-serving imbeciles like the ‘leadership’ currently controlling this Midlands district.”

While parental involvement will always be an essential component in helping ensure that competent individuals take leadership positions in schools, I’ve learned it isn’t always enough. Years of continued incompetence and misfeasance in Richland district one illustrate this point well. In 2016, superintendent Craig Witherspoon (who makes more than $235,000 a year) missed a title one funding deadline that cost his district more than $3.1 million. In 2019, Richland district one was accused of awarding major contracts to businesses connected to board members. Six months ago, the district was sued for the second time in two years for allegedly holding secret meetings in violation of the law.

Without an independent body vested with the authority to hold these administrators accountable why would any reasonable person expect this pattern to change?

Full P-card report:

***

ABOUT THE AUTHOR …

(Via: Travis Bell)

Dylan Nolan is the director of special projects at FITSNews. He graduated from the Darla Moore school of business in 2021 with an accounting degree. Got a tip or story idea for Dylan? Email him here. You can also engage him socially @DNolan2000.

***

WANNA SOUND OFF?

Got something you’d like to say in response to one of our articles? Or an issue you’d like to proactively address? We have an open microphone policy here at FITSNews! Submit your letter to the editor (or guest column) via email HERE. Got a tip for a story? CLICK HERE. Got a technical question or a glitch to report? CLICK HERE.